Make an “Anything-Product"

How to transform your product's market size from $100M to a $100B

Welcome to the 863 newly Startup Builder people who have joined us since last essay! If you haven’t subscribed, join 5,725 smart, curious founders, investors, and startup enthusiasts by subscribing here:

Hey! 👋

This is Startup Builder by Henrik Angelstig. Every week I consume countless hours of books and podcasts on entrepreneurship to learn why some startups succeed while others don’t. 📚

I then distill the most non-intuitive lessons into short essays. Bringing you the most useful insights that fewest founders know.

In today’s essay, we’ll be discussing market size – how to increase it, and how to evaluate it.

Make an “Anything-product”

Market size is arguably the main driver of a startup’s success.

With enough demand, a startup can succeed despite terrible execution and lots of competition. A large market is also the #1 thing VCs want to see when investing.

As Sequoia’s founder, Don Valentine, said:

“I like opportunities that are addressing markets so big that even the management team can’t get in its way.”

But big markets also have a dark side:

They are highly fragmented.

Take the food industry as an example.

In 2022, the global food and groceries market was estimated at more than $11 trillion.1 But this enormous pie consists of millions of different slices of food products. The market size of any single slice is likely too small to interest a startup.

A startup, however, doesn’t have the luxury of building multiple products. It must concentrate all its efforts on a single one. This leaves us with a problem:

How can a startup attack a big market’s many fragments with just one product?

The answer is to build an “anything-product”.

As the name suggests, an anything-product is something that can be used by anyone, for anything, at any time.

Let’s look at the company Venmo as an example.

Venmo: A story from specific to anything

Venmo is one of the leading mobile payment processors in the U.S. People use the app to send money for every product or situation imaginable. In 2022, $230B changed hands via their platform.

But Venmo didn’t start that way.

The original idea was to let musicians accept payments for live gigs and merchandise.

With a product that specific, the market size was incredibly tiny.

The founders therefore decided to pivot Venmo to let anyone accept payments for anything, at any time. They made Venmo an anything-product.

And just like that, Venmo’s market size was transformed from a few million – to hundreds of billions of dollars.2

The Venmo story illustrates the power of an anything-product.

Venmo could never have made a specific product for every imaginable situation where money needed to be sent.

But they didn’t need to.

Venmo just had to make one great product that could send money for anything.

That is how one product can attack all the fragments of a big market.

Understanding big markets: the pie with a million flavors

Big markets are like pies divided into a million different slices. Each slice with its own unique flavor. The million different flavors represent the specific products on the market.

For the food market, the flavors may be a McDonald’s hamburger, spaghetti bolognese, Ben & Jerry's ice cream, etc.

Most entrepreneurs look at the big pie and say: “I see a flavor that’s missing!” and build a product to add that flavor to the pie.

Their new product will steal some customers – who prefer the new flavor – from the other slices. The new product will also grow the whole pie by attracting a few new customers who weren’t satisfied with any of the existing flavors.

However, it’s impossible to build a big business around one specific flavor.

Flavors are, by design, specific. Change a flavor, and the value proposition is no longer the same. But this specificity is precisely what constrains the specific product’s market size.

Don’t add flavors. Make it easier to produce or consume more pie

In contrast, the anything-product doen’t add any new flavor to the market pie. Instead, it aims to be the sugar with which the whole pie is baked, the plate on which the whole pie rests, or the oven in which the whole pie is baked.

The anything-product is something that makes it easier to produce or consume pie.

Take IKEA as an example. IKEA does not produce all the millions of furniture flavors they offer. They make furniture cheaper and more convenient to buy. Their anything-product is a ferociously cost-efficient supply chain and massive stores. IKEA can push any product through this supply chain, get it to any customer through its stores, and do it at a lower cost than anyone else. IKEA is a company that makes it easier to consume pie.

Another example of an anything-company is Dropbox. Dropbox does not create any of the data that they store. They just make it more effortless to store data and share it with others. Their anything-product is the servers and the drag-and-drop folder that allows you to store anything. Dropbox is a company that makes it easier to produce pie.

To attack a big market, don’t think about adding a new flavor.

Think about how you can help consumers to consume or producers to produce.

That way, you get a share of every flavor in the pie.

How to make a product more “anything”

The two levers

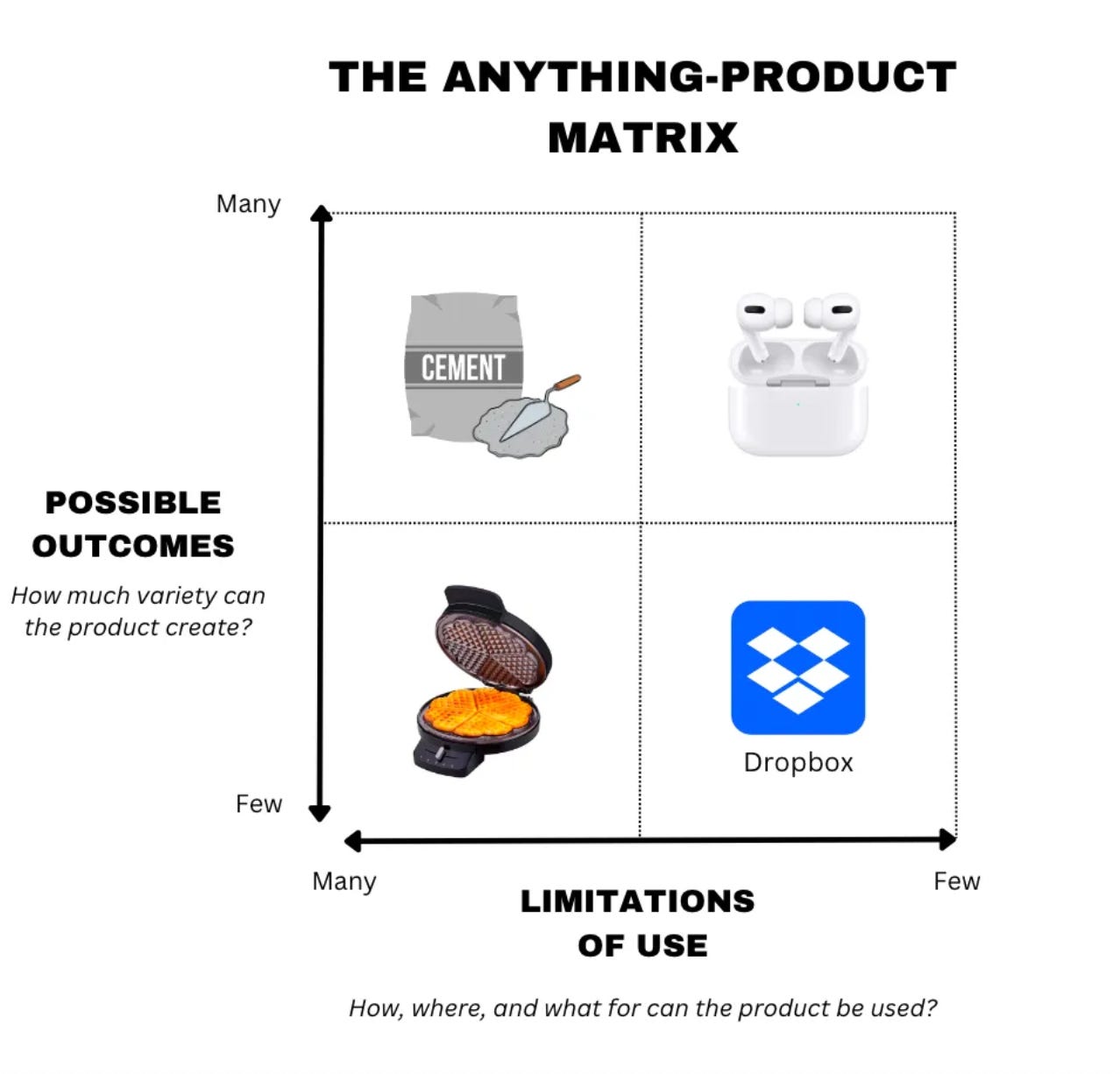

So how do you make a product more “anything” to maximize its market potential? There are two levers that underpin the anything-product that you can play with:

Many possible outcomes

How much variety can the product create?Few limitations of use

How, where, and what for can the product be used?

Cement is an anything-product that scores well on the outcome lever – but not the limitation lever. Cement is very durable and can be shaped into any form possible, which is why it’s one of the world’s most used building materials. However, cement is also heavy to transport and impossible to remodel once it has fixed, which is why it’s rarely used for anything but buildings. Cement has many possible outcomes, but many limitations of use.

Dropbox is a product that scores well on the limitation lever – but not the outcome lever. Dropbox can be used to store any kind of file. But there is no variation in the outcome Dropbox produces. You store and share a file, and that’s it. Dropbox has few limitations of use, but few possible outcomes.

AirPods is a product that scores high on both levers. It can be used to play any song, podcast, or sound imaginable. And they are so small with so much battery that they can be used anywhere, at any time, and for long periods of usage. AirPods have both many possible outcomes and very few limitations, which is why Apple’s sales of AirPods is so large that – if broken out – would equal a Fortune 500 company. 3

Contrast these products to a waffle maker, which can create a very limited set of outcomes, and have high limitations on where and what for it can be used.

Expanding the market for a product is a challenge in creativity. It’s about discovering novel ways to push the boundaries of your product’s:

Possible outcomes, or

Limitations of use.

We can boil market size down to this simple formula:

Market size = #Possible outcomes – Limitations of use

How to expand the outcome lever

The outcome lever often seems impossible to expand. Take a microwave as an example. You can change the intensity and the duration with which a meal is heated. But a microwave has just that one function: heat.

So how do you expand beyond that core function? There are two strategies entrepreneurs can use:

1. Integrate – Build another anything-product into your product

The “integration” strategy is how Apple made the iPhone. If you just make a phone portable, you reduce the limitations lever. But you don’t expand the outcome lever.

However, if you bundle a phone with:

A touch screen – that can display any content or interface

A camera – that can capture any scene

An internet connection – that lets you interact with anything or anyone on the web

…The possible outcomes your product can create is multiplied by 1000X.

In fact, the sum of the anything-products is often more than the sum of its parts, because of the countless ways they can be combined. For example, the camera would not be nearly as valuable without the internet connection that allowed you to share these photos.

If you can’t expand the heating of your microwave, then find a way to build another kitchen product into your microwave.

2. Go lower – Pivot to making the building blocks of your product

The “go lower” strategy is how LEGO became a success. Most toys are monolithic pieces – many materials combined into a single fixed thing. But give kids LEGO bricks – small building blocks that can be combined in infinite ways – and you give them the power to create anything.

Every anything-product is actually built from this “go lower” strategy.

Look at anything you use a lot in your daily life. You’ll find that it consists of just a few different building blocks that are repeated and combined in a million ways:

The English language? Just 26 letters.

Digital data? Just two digits: 1 and 0.

The whole universe? Just three building blocks: electrons, protons, and neutrons. (Not counting dark matter)

Of course, at some point the building blocks may become so small we can’t actually use them in production. But the lower you can go, the more outcomes you can create, and the larger the market potential for your product.

If you can’t expand the heating of your microwave, focus on making just the magnetron that creates the heating waves in the oven.

Since magnetrons can be used to build many more products besides microwave ovens, the market size for magnetrons is much bigger than the market size for microwaves.

How to reduce the limitation lever

Sometimes the limitations of a product are obvious. These are the moments when we wish we could use the product but can’t. But at other times, we are so used to the limitations of the whole product category that we are not even aware that the limitations are there.

Take the telephone as an example. At first, people were so amazed they could talk to others hundreds of miles away they were not even aware of how limiting a stationary phone was. To not fall into this trap ourselves, here is a…

Checklist of limitations to consider:

Size: Make it smaller

Weight: Make it lighter

Speed: Make it faster

Mobility: Make it portable

Power: Minimize its energy consumption and maximize its battery life

Environment: Make it withstand heat, cold, wet, and dirt

Once a product can successfully do its basic job well (and with no irritating side effects), I argue that the #1 limitation of a product is its size.

Why?

Because if a product is small, it tends to reduce all the other limitations as well. Small products weigh less, are more portable, have fewer components that can break, and consume less energy.

In fact, many small modules can be even faster – and have greater capacity – than one big bulky product.

A Tesla battery, for example, actually consists of thousands of small battery cells. And together, they make for one hell of an engine! 4

Set out to build a Swiss army knife.

But start by selling a corkscrew

The anything-product has two obvious downsides.

First, it can be overwhelming to build, because they must be able to accommodate so many more use cases.

Second, it can be incredibly hard to sell, because the customer can’t understand what specific thing to use it for.

How to overcome this problem? Start with selling just one specific flavor of the product.

In the long run, the goal is to build a Swiss army knife.

But right now, just build and sell a corkscrew.

Take Amazon as an example. Today, you can buy nearly anything on amazon.com. But Jeff Bezos started just with books. Because books:

Vary enormously in content, so there is a huge market that can be satisfied

Have a low price tag, which make them a low-risk purchase

Are small and durable, so they can be shipped cheaply with few damages

Jeff Bezos deliberately picked a corkscrew that:

Met an immediate customer need,

Was easy to supply, and

Was itself a large market.

Those are the three traits to look for when deciding what tool in the Swiss army knife to sell first.

Anything isn’t enough – It must be a better anything

Having an anything-product does not mean you have a great business. It only means that you have a large market potential. To capture that market you must be a better anything-product than the competition in some way: price, speed, quality, etc.

Again, we can learn from Amazon.

By focusing exclusively on books, Amazon reduced its competition to just brick-and-mortar bookstores – over which Amazon had an advantage in price, convenience, and selection.

This advantage enabled Amazon to make a profit on their corkscrew (books), so they could then add the next tool to their Swiss army knife (music CDs).

This is key. A startup must sell a product where they have an edge over the competition. If your corkscrew lacks a competitive edge, then try the tweezers.

Don’t expand to more tools before you are the sharpest in any one of them. If every tool is blunt, it doesn’t matter how many of them you got.

Lessons for investors

Being able to spot anything-products early is one of the greatest edges an investor can have.

Why?

Because the market potential for an anything-product is often 10X, 100X, or even 1000X greater than people first assume.

When Apple came out with the iPhone in 2007, who would ever predict, that 15 years later, iPhone sales would be more than $200B a year? For a single product!

But had you scored the iPhone on how great an anything-product it was, it’s actually obvious that its market size would one day be nearly limitless.

If you have a product that can:

Call anyone,

Display any content or interface,

Photograph any scene,

Interact with anything or anyone on the web, and

That you can carry around with you and use whenever you want

…There is almost no limit to how many units of that product you can sell.

Instagram is another case example.

When Mark Zuckerberg bought Instagram for $1B when the app had just 30 million users, most people thought he was nuts.

But let’s score Instagram as an anything-product.

The app had huge variation in outcomes: it could be used to capture any photo, make it prettier with filters, and share it with anyone.

As a mobile app, there were practically no limits to when or where Instagram could be used.

12 years later, and Instagram is now cashing in $50B+ a year, and still growing strongly. 5

The anything-product concept is especially important for angel investors and VCs, for whom market size is arguably the most important factor.

Learn to spot anything-products, and you have a huge edge over everyone else who can’t.

Closing

Anything-products rule our world.

Look at anything you use a lot daily – the English language, your smartphone, money, steel, running water – and you will always discover an anything-product.

But if there’s one main takeaway for entrepreneurs, it’s this:

It’s just as hard to do something big as to do something small.

No matter what product you choose, the world is going to resist it with all its might. You are going to work yourself to the bone no matter what. So why not make an anything-product that – if successful – would have a vastly bigger impact?

How much bigger could your vision be if your product could be used by anyone, for anything, at any time?

I hope you found this essay useful,

Henrik Angelstig