How to Unite Opposites Into Greatness

The 3 ways great founders achieve extreme results AND balance

Welcome to the 2,091 newly Startup Builder people who have joined us since last essay! If you haven’t subscribed, join 13,101 smart, curious founders, investors, and startup enthusiasts by subscribing here:

Hi! 👋

This is Startup Builder by Henrik Angelstig. Every week I consume countless hours of books and podcasts on entrepreneurship to learn why some startups succeed while others don’t. 📚

I then distill the most non-intuitive lessons into short essays. Bringing you the most useful insights that fewest founders know.

Today’s essay will cover how to unite opposite approaches into greatness – and why you always need a counter-balancing yin to every yang.

How to Unite Opposites Into Greatness

If there’s one quality of great entrepreneurs, it’s embracing seemingly contradictory ideas.

Steve Jobs exerted his will forcefully AND remained open to others’ ideas.

Warren Buffett combined extreme patience AND quick, decisive action.

Jeff Bezos could go ballistic on a $10 expense AND ok a $10M expense without blinking.

However, few leaders united opposing strategies better than Alexander the Great.

In 334 B.C., Alexander led an army of 35,000 Macedonians into the western area of the Persian Empire. Their first battle was a crushing victory against the Persians, thanks to Alexander’s bold and quick maneuvers that seized the initiative.

His troops now expected him to follow this daring approach. To march east and strike at the heart of the weakened Persia before they had time to recover.

But Alexander did the opposite.

He took his time.

Alexander instead led his army south and began freeing local towns – and then Egypt – from Persian rule. The Egyptians, who despised the Persians, welcomed Alexander as their liberator. Instead of conquering the Persian army, Alexander snatched a key resource from Persia’s hands: Egypt’s vast stores of grain.

However, the Macedonian army was now exposed to the Persian navy, which might land an army at any port along the coast and attack them from behind. Alexander was expected to build his own navy and take the fight to them.

But Alexander did the opposite.

He captured the Persian ports, and rendered the enemy fleet useless.

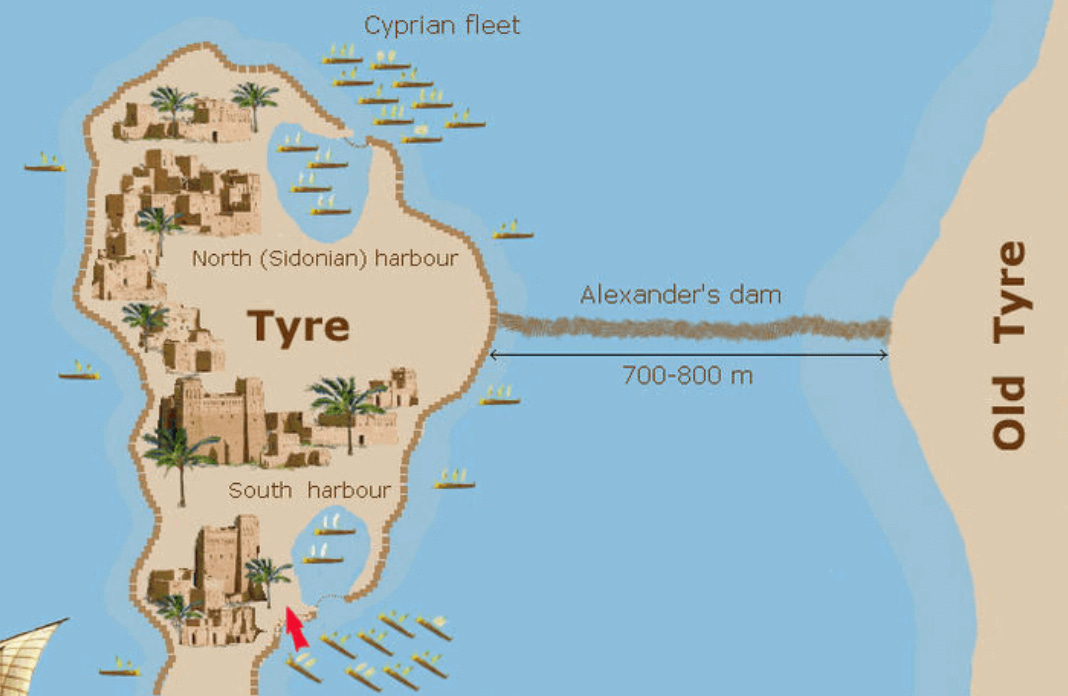

Still, one Persian port held out: the stronghold of Tyre. Located on an island and shielded by stone walls 150 feet high, it was deemed impenetrable. Since Alexander recent strategy had been to attack the enemy’s soft targets, surely he would leave Tyre alone?

But Alexander again made the opposite move.

He had his army build a half-mile-long causeway all the way out to the island. He laid siege to Tyre for months until they finally broke through the city’s walls.

With the success of this brute-force approach, he would surely spread the Macedonian rule and march east to pursue the Persians?

But, once again, Alexander did the opposite.

He began focusing on politics, adopted the Persian culture, and built upon the systems in place. He demanded the same tributes. But changed only the unpopular parts of Persian rule.

Word soon spread of Alexander’s compassion toward his new subjects. Town after town gladly surrendered to the Greeks without a fight.

Then, finally, Alexander faced the Persian army head-on in the Battle of Gaugamela.

But by this point, the Persian Empire had already fractured without the Egyptian grains, their navy, and the tributes from their cities.

Weakened and out-strategized, their army was defeated by Alexander despite their greater numbers. 1

To everyone else, Alexander’s approach seemed to have no consistency. He was both:

Merciless AND gentle

Direct AND indirect

Forceful AND adopting

It was because he embraced opposing ideas that he made his success.

What great leaders like Alexander do often seems like magic. By swinging from one extreme to the next, they somehow accomplish more than everyone else.

But how can we “normal” people do the same – and unite opposing ideas into greatness?

This essay aims to cast some light on that question.

But first, we must clarify three important truths about Yin and Yang.

Three Truths About Yin and Yang

Chinese philosophy uses Yin and Yang to symbolize the balance of two seemingly opposing ideas.

However, this concept is often misunderstood in the Western world. I therefore want to clarify some common misconceptions to create a clearer understanding of what “balance” means.

1. Yin and Yang are complements with the same goal. Not opposites with different goals.

A common mistake is to view Yin and Yang – expansion and constraint – as two opposing forces, one coming at the expense of the other.

This completely misses the point.

Both Yin and Yang seek to achieve the same goal: to thrive.

And it’s because Yin and Yang bring complementary strengths that the goal of thriving is achieved.

Take marriage for example. Are the partners two “opposing” forces? Of course not! They both share the same goal of thriving together. And in the best marriages, the partners complement each other’s weaknesses with their own strengths. That is why they thrive together.

Similarly for a startup, are exploration and exploitation two “opposing” forces? Of course not! They both share the same goal of increasing revenue so the startup can thrive. And in the best startups, exploration and exploitation are viewed as complementary approaches to that singular goal.

By being both Yin and Yang, you are not contradicting yourself by pursuing different goals.

You are pursuing the same goal – to thrive – and complementing Yin with Yang increases your chances of achieving it.

2. Yin-Yang means reciprocity within the internal, but balance with the external.

Every single thing is a system of multiple parts. A company, for instance, is a system of customers, employees, suppliers, and shareholders.

What holds any system together is reciprocity – when each part gains more from the other parts than it could achieve on its own. Mutual reciprocity is what ties all the individual nodes in a company, a network, or a community together into a unified whole.

At the same time, a system must achieve balance between itself and its external environment. The human body is a perfect example:

When exposed to excessive heat, it sweats to counterbalance the warmth.

When food is scarce, it limits its energy expenditure.

When threatened by a predator, it spikes its adrenaline to prepare for fight or flight.

Balance should always be relative to the external environment. Not between the internal parts.

When the human fight or flight system kicks in, the body suppresses the digestive system to conserve energy for its muscles.

Is the digestive system being shortchanged here?

Of course not!

Both muscles and digestion share the same goal of not being eaten. But the muscles are better suited to the external threat than the digestive system. Prioritizing one part directly ends up benefitting both indirectly.

A company that must “balance” the interests of its stakeholders is simply a poorly organized company. The real problem is a lack of reciprocity or confusion about the shared goal.

Few systems have achieved both internal reciprocity and external balance better than Berkshire Hathaway.

By combining cash-flowing businesses with insurance companies, Warren Buffett created a compounding flywheel of internal reciprocity.

The cashflows from the businesses provided greater financial safety for the insurance companies. This let them lower their prices and attract more customers who bought insurance. The cash from the insurance could then be reinvested into buying even more cash-flowing businesses. And so on. 2

At the same time, Buffett created external balance through his investment strategy: “Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” He could wait years without making a hardly single investment, patiently waiting for the right opportunity to present itself.

And then, when the financial crisis of 2008 struck, Buffett deployed $8 billion within 4 weeks. Followed by another $38 billion in 2009. 3 4 5

Balance often looks like a whipsawing imbalance of action. Not moving a muscle for years, and then striking with a decisive and lightning-fast blow doesn’t seem balanced. But it was a perfect balance relative to the environment that Berkshire Hathaway faced.

The external environment is rarely “balanced”.

Therefore, your response should rarely be “balanced” either.

Only by countering external imbalance with an equal imbalance of action will you buffer to maintain internal balance for yourself.

3. Do Yin and Yang with excellence – but do them separately.

Great entrepreneurs adopt a dual-excellent approach, where:

In each instance, they are either highly Yin or highly Yang.

But on the whole, they make use of both.

They never “compromise” black and white into a greyish muck. By taking each approach to a level of extreme greatness – but doing it separately – they maximize the unique benefit of each approach AND maintain balance.

This dual-excellent approach is common to every example of greatness:

A great partnership is when one is highly big-picture AND the other is superbly detailed.

A superb leader sets specific expectations AND gives total freedom for how to achieve them.

A stellar speech-maker will go high and fast AND follow with a slow and silent pause.

Greatness is never EITHER/OR.

It’s BOTH/AND… but separately.

One entrepreneur who utilized this dual-excellence strategy is Sam Bronfman, the founder of Seagram’s Whisky.

Bronfman’s philosophy on finances was: “Spend no money. But when you do, go first class.” He was stingy to the core with turning off office lights and getting mad at employees who spent money on things that weren’t needed.

But when Bronfman needed advertising, packaging, or hiring – we would spend as much as necessary to get the highest quality possible. 6

This echoes Warren Buffet’s strategy of: “Don’t invest. But when you do, go big.”

Three Ways to Unite Opposites Into Greatness

Having clarified Yin-Yang “balance” I want to leave you with three ways to pursue both approaches in practice.

1. Improve Yin by improving Yang

As entrepreneurs, we are overwhelmed with issues, goals, and KPIs that we all want to solve simultaneously.

The solution is to understand the knock-on effects between one part and another. Knock down the right domino, and you can indirectly topple the whole row of issues.

There are two kinds of systems where knock-on effects occur: pyramids and flywheels.

1.1 Pyramids

A pyramid is a system with one-directional knock-on effects: improving A ⇒ improves B ⇒ improves C. But it doesn’t work the other way.

A tree is one example. By treating the sick roots, you can cure the half-dead leaves. But treating the leaves will not cure the roots.

In his book The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni describes the 5 components a team needs to succeed as a pyramid – and how the absence of one component will make the rest on top collapse too.

The Five Dysfunctions are:

Absence of Trust ⇒

Fear of Conflict ⇒

Lack of Commitment ⇒

Avoidance of Accountability ⇒

Inattention to Results

The book is a business fable where a new CEO comes in to turn around a failing company. But instead of focusing on strategy, the CEO recognizes that the root problem is a dysfunctional leadership team, caused by an absence of trust.

By strengthening trust in the leadership team – and then the remaining four components – she ends up solving all the company’s subsequent problems too.

Look closely, and you’ll find pyramid systems all around you. The key to recognizing them is to ask: “What created this outcome?” or “What would make X easier to achieve?”.

This is why great founders obsess over hiring. Employees are the ones who create every output – good or bad – in the company.

To strengthen your whole company, start by strengthening your team.

1.2 Flywheels

A flywheel is a feedback loop with two-directional knock-on effects: improving A ⇒ improves B, and improving B ⇒ improves A.

One example is the “Belief 🔄 Ability” flywheel.

A common saying is that: “Belief comes before ability.” David Senra, host of the Founders podcast, has read 300+ biographies of entrepreneurs. And he mentions that this theme comes up time and time again: People who do great things believe they are champions before they do it.

However, you can also act your way into self-belief.

When Captain David Marquet took over command of the U.S. nuclear submarine Santa Fe, it was the worst-performing ship in the entire U.S. fleet. The crew believed they were losers, and so they acted like it.

But instead of turning the crew’s self-belief around, Captain Marquet asked his officers:

“How would we know if the crew were proud of this boat. What would we observe?”

After a silence, his officers responded:

“They’d brag about it to their family and friends!”

“They’d look visitors in the eye when they met them in the passageway!”

“They’d wear their Santa Fe ball caps as much as possible!”

MARQUET: “Well, what if we just tell them to act that way? What if we just tell them to greet people respectfully, sincerely, and proudly?”

That’s exactly what they did. And it worked! They faked it until they believed it. 7

In a flywheel, it doesn’t matter which part you feed. Just pick whichever area you can start acting on most easily.

2. Switch between fully Yin and fully Yang to fit the situation

In June 1812, Napoleon led his immense army of 450,000 men into Russia, determined to conquer the vast country.

Being hopelessly outnumbered, the Russians refused to face Napoleon in direct combat. Instead, they kept retreating further and further into the vast emptiness of their country, forcing Napoleon’s humungous force to chase after them.

But Napoleon’s large force was too slow to catch up. And as the Russians retreated, they burned all resources left behind, leaving a barren wasteland behind them.

With the harsh Russian weather and lack of supplies, Napoleon’s men started dying by the thousands. But he refused to turn back. Not until they reached an abandoned Moscow, with the bitter Russian winter encircling them, did Napoleon finally retreat.

Of the 450,000 men Napoleon led into Russia, less than 25,000 returned. 8

What caused Napoleon’s downfall was his failure to switch approaches to fit the situation.

Most traits can be sorted into one of two categories.

Expansive traits that promote growth, energy, and possibilities:

Flexible

Bold

Curious

Constraining traits that limit growth, energy, and possibilities:

Stubborn

Paranoid

Disciplined

The key is to combine decisive expansion AND firm constraints.

To pursue bold growth AND focus your efforts and never go too far.

Napoleon had previously switched approaches to fit the situation. That was how he achieved his victories. It was his failure to do so in Russia that led to his defeat.

3. Be fully Yin in one part, and fully Yang in another

Every concept is a sum of many parts. Great entrepreneurs recognize this fact and seek to be fully Yin in one area AND fully Yang in another.

Jeff Bezos is famous for saying: “Be stubborn on the vision but flexible on the details.” He recognized that great execution consists of both vision AND details, which allowed him to be stubborn in one aspect AND flexible in the other.

Richard Branson recognized marketing and finances as two separate parts of his business. And while he has been audaciously daring in the first, he has been extremely conservative in the latter.

When Branson started Virgin Atlantic, he was so determined to cap his downside that he convinced Boeing to lease him a secondhand 747-plane for a year to test the concept, instead of taking the normal risk of buying a plane outright.

However, when it came to marketing against the incumbent airline, British Airways, it was “Screw it, let’s do do it!”. Branson dressed himself up as a pirate outside BA’s most profitable airport, Heathrow, and declared it “Virgin Territory”. He then decided to set a world record by being the first person to cross the Atlantic in a hot-air balloon. 9 10

By seeing every concept as a sum of many parts, you can be fully Yin in one part AND fully Yang in another.

Closing

Greatness is the collaboration of complementary ideas.

However, it’s hard to grasp how to unite seemingly opposite approaches unless you understand these three important truths:

Yin and Yang are complementary partners with the same goal.

Yin-Yang means reciprocity within the internal, but balance with the external.

Do both Yin and Yang with excellence – but do them separately.

To adopt this concept in practice:

Realize how one part affects another,

Identify what situation you face in each moment, and

See each thing as a sum of many parts.

With this nuanced view, you can be fully Yin or Yang in each part AND embrace both in the whole.

Then, you’ll be ready to unlock greatness too.

Thanks for reading,

Henrik Angelstig

The 33 Strategies of War – by Robert Greene

Turn the Ship Around! – by David Marquet

The 33 Strategies of War – by Robert Greene