Bright Spots: How to Sail to Success Despite an Ocean of Obstacles

How focusing on positive outliers lets you triumph in spite of a negative environment

Welcome to the 1,655 newly Startup Builder people who have joined us since last essay! If you haven’t subscribed, join 14,756 smart, curious founders, investors, and startup enthusiasts by subscribing here:

Hi! 👋

This is Startup Builder by Henrik Angelstig. Every week I consume countless hours of books and podcasts on entrepreneurship to learn why some startups succeed while others don’t. 📚

I then distill the most non-intuitive lessons into short essays. Bringing you the most useful insights that fewest founders know.

Today’s essay will cover bright spots – and why focusing on positive outliers is the best way to reach your goal despite an ocean of obstacles.

Bright Spots: How to Sail to Success Despite an Ocean of Obstacles

How do you achieve a breakthrough on a shoestring budget – in an environment where everything is working against you?

That was the challenge that Jerry Sternin had to solve in 1990’s Vietnam. He was working for the human aid organization Save the Children, which had been invited to Vietnam to help combat the widespread malnutrition among the nation’s children.

When Sternin arrived in rural Vietnam, he met with a grim, ocean-sized problem:

More than half of the population lived on less than $2 per day. 1

Clean water was rarely available.

Sanitation was bad.

Rural people had little knowledge about nutrition.

To make matters worse, Sternin had hardly any resources, only a handful of team members, and the Vietnamese government was breathing down his neck and demanded improvements in just 6 months.

And yet… 6 months after Sternin arrived in the Vietnamese village where he conducted his pilot program, 65% of the children were better nourished.

How was Sternin able to turn the situation around so dramatically, so fast, and with so few resources?

Because he looked for bright spots. 🔆

Sternin knew he couldn’t change the structural problems he faced. Raising incomes or improving clean-water access would have improved the situation. But these problems weren’t actionable.

Instead, he looked for positive outliers – kids who were already well-nourished despite the challenging environment.

This approach led Sternin and his team to some surprising insights.

They found that healthy kids:

Ate shrimp and crabs which their mothers collected from the rice paddies. Shellfish wasn’t considered suitable for children, but it provided much-needed protein.

Were fed 4 smaller meals a day, instead of 2 larger meals that most families ate. Kids’ malnourished stomachs couldn't handle that much food in one go.

Were actively hand-fed by parents, rather than feeding themselves.

Sternin then turned these insights into a village cooking session – led by the bright-spot moms – to teach these principles to the whole village. Through these sessions, the moms were "acting their way into a new way of thinking.”

The program was later rolled out to 265 villages, reaching 2.2 million Vietnamese. 2

Sternin wasn’t an entrepreneur. But his context was nearly identical to a startup. He had:

Countless factors working against him

Hardly any resources at his disposal

A tight deadline to deliver results

But despite these tough odds, he turned the situation around with a simple approach:

Find and replicate bright spots.

The term “bright spot” was first coined by Chip and Dan Heath in their amazing book Switch: How To Change When Change Is Hard. I can’t recommend it enough!

In this essay, I want to cover 3 lessons that I believe we can learn from Sternin’s story:

Bright spots are your lighthouse through the foggy ocean of problems

To make a big change, don’t focus on what’s bad. Replicate what’s great.

To replicate bright spots, find the specific actions they do differently from the rest.

Let’s dive into each of them.

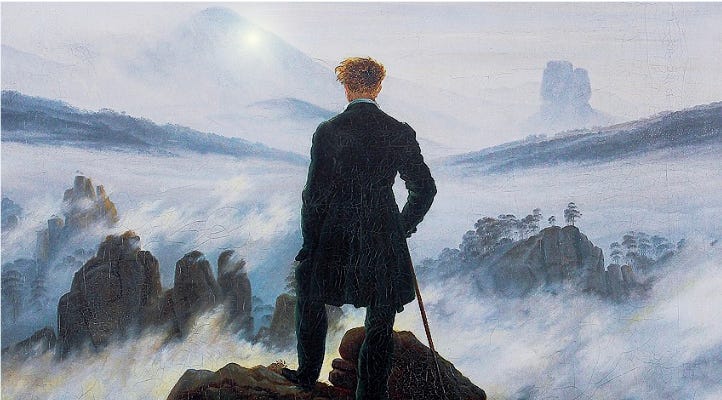

1. Bright spots are your lighthouse through the foggy ocean of problems

When you face any daunting challenge – such as building a startup – it's helpful to think of yourself as a sailor, and the challenge as crossing a vast ocean covered in thick fog.

The fog is the murkiness of reality. We rarely see the islands of opportunity or the threatening reefs ahead until we are upon them.

The ocean is all the large and overpowering forces outside of your direct control. The ocean may be your competitors, the market, or even a bad habit. The ocean acts on you – for better or worse. It may give you a boost to greener lands, or toss you around like a leaf in a storm.

When the ocean acts against us, it often feels like the ocean itself is the problem – and we throw our hands up in despair. When Sternin arrived in Vietnam, he could easily have let himself be overwhelmed by the ocean of widespread poverty and poor sanitation.

However, Sternin chose to ignore these “problems” because they weren’t actionable. He couldn’t change them any more than change gravity.

The ocean is never the problem – because you can’t do anything to change it.

The real problem is the fog – that you can’t see which action is best to take.

This is why bright spots are so important. Like a lighthouse, they shine a light in the direction that best gets you toward your goal.

2. To make a big positive change, don’t focus on what’s bad. Replicate what’s great.

We humans are hard-wired to focus on the negative. But focusing on what’s bad rarely works when you aspire to make a big change.

Why?

Because any big challenge has been caused by an ocean working against you. If the ocean was working with you, you wouldn’t have a challenge to begin with.

By focusing on what’s bad, you draw your attention to the problematic ocean – which you can’t do anything about.

You must find a way forward despite the ocean – and that way forward is to find and replicate bright spots. 🔆

Sternin didn’t turn around the situation in Vietnam by fixing all the problems. Instead, he focused on kids who were healthy despite the challenges, and simply replicated what they did differently.

Let’s look at two more stories of bright spots.

Law firm – How one extra team member turned failing projects around

The lawyer Andrew was frustrated.

He and his colleagues often met to discuss new initiatives to grow the business long-term. They had many good ideas. Yet after every such meeting, they were sucked right back into the whirlwind of short-term emergencies.

It looked like the long-term projects would never take off.

But then Andrew remembered one successful idea that stood out. What was different?

An associate, a rising star, had been part of that meeting and took the idea forward.

Unlike partners, associates had a strong reason to work on long-term projects – to impress the partners and outshine their peers.

Andrew had found his solution:

Involve a talented associate in every long-term brainstorm. 3

Genentech – Failing to replicate a 20X sales strategy

In 2003, Genentech launched a drug called Xolair. It was considered a "miracle drug" for asthma – far better than existing alternatives.

But 6 months later, sales of Xolair were far below expectations.

When Genentech investigated the problem, they found two saleswomen who were selling not 2X, not 5X, but 20X as much Xolair as their peers.

Instead of selling the health benefits of Xolair – which doctors understood – they were teaching doctors how to administer the drug.

Xolair was not a pill or an inhaler. It required infusion via an intravenous drip. This technique was unfamiliar to most doctors – and that uncertainty was holding back 95% of doctors.

When the Genentech managers discovered these bright-spot saleswomen, they rejoiced and immediately spread the sales strategy to all their salespeople, right?

Sadly, no.

The managers instead treated these women’s success with skepticism! They assumed the women had some unfair advantage, and their first reaction was to readjust their sales territory.

This story is a warning. ⚠️

We are so prone to look for the negative, that even success can look like a problem. 4

When you face an ocean-sized problem, look for a one-person solution

In these stories, notice how tiny the solution is compared to the oceanic scale of the problem:

This asymmetry is very counter-intuitive for most people. When faced with an ocean-sized problem, we tend to look for an ocean-sized solution.

Bright spots defy this “logic”. They use ordinary actions that can be done by a single person – and replicate them to achieve extraordinary results.

Whenever you face a problem, I urge you to ask this question:

“Is this a problem with a simple solution?”

If “no”, then look instead for bright spots.

Here are some examples of how to turn a problem into a search for bright spots:

Our customer satisfaction scores are terrible. Except for these 5 customers who gave us glowing reviews. 🔆

Sales leads are falling everywhere. Well, apart from our YouTube channel where leads grew by 15%. 🔆

New hires are quitting after a just few months. Except for the recruits in Greg’s team who have stayed for 2 years. 🔆

3. To replicate bright spots, find the specific actions they do differently from the rest.

When you find a bright spot, how do you replicate it?

To answer this question, you must understand 2 key things about bright spots:

Bright spots are the result of specific actions…

…That are different from what the average does.

Look again at the solutions from the stories above:

✅ Feed kids shrimp.

✅ Include a talented associate in brainstorms.

✅ Teach doctors how to administer the drug.

These aren’t vague statements like “Provide a balanced diet” or “Support young talent”. They are specific actions that can’t be misinterpreted. This specificity is why bright-spot actions work – they are easy to follow despite a stormy and foggy ocean.

However, most actions a bright spot does is nothing special. When Sternin studied well-nourished kids in Vietnam, he found that they were all fed rice. But all the malnourished kids were fed rice too. Eating rice didn’t differentiate success from non-success.

Sternin was only able to identify the key nutrition practices because he also studied families that didn’t have well-nourished kids. In the average Vietnamese family, kids:

Didn’t eat any seafood.

Were fed 2 times a day.

Were relied on to feed themselves.

These “average actions” became the benchmark. Only then could Sternin see which actions were causing the superior health of the bright-spot kids.

You can’t predict bright-spot actions. You can only discover them by studying real bright spots.

In the book The 4 Disciplines of Execution, the authors share the story of how they helped a large US’s shoe retailer – with 4,500 stores – to improve their sales. The authors advised them to first study their bright-spot sales clerks to see what they did differently.

Can you guess what the most important action to increase shoe sales turned out to be? Was it to:

Offer friendly service?

Increase speed at check-out?

Reduce the number of out-of-stock items?

Nope.

The best predictor of increased sales was measuring children’s feet.

As the authors explain:

“Imagine you are the adult responsible for the back-to-school shoe buying adventure. You have multiple children with different shoe sizes, distinct preferences for style and color, and a very limited tolerance for shopping – all needing shoes today.

At that moment. a salesperson approaches you and offers to measuring the children’s feet to ensure quality fit, before showing each child a selection that matches their preferences and your budget.

What would your reaction be? Especially in an industry were customer service is often sacrificed for lower prices and faster checkout times?” 5

Now, imagine if the authors had walked into the boardroom and proudly announced: “We know how to improve your shoe sales – tell every sales clerk to measure children’s feet!”. They would have been laughed at.

And that’s the point:

Small actions that make big success are not intuitive.

Feeding kids shrimp was not intuitive.

Including an associate in brainstorms was not intuitive.

Teaching doctors to administer the drug was not intuitive.

If a simple solution was obvious, everyone would already be doing it.

This is how the ultimate resourceful entrepreneur triumphs over their bigger competitors.

Not by out-working them.

Not by out-smarting them.

But by out-bright-spotting them.

How to find bright spots – 3 ways to get more data points

Bright spots are rare. The only way to find them, and to realize when you have them, is to collect more data points.

Here are 3 different ways to expand your dataset:

1. Personal experience: Have you beaten the ocean before?

Tania and Brian was a married pair that – like all couples – occasionally got into fights. But their fights often turned needlessly sour.

Their initial approach to solve the problem was to analyze why their fights got so bad. But as you likely know by now, focusing on the negative ocean rarely works.

Even if you figure out why the ocean current is pushing your boat back – you still can’t do anything to change it.

What did work was to find a bright spot. As Tania explained:

“One day we had conversation over breakfast about our budget—and it was so smooth and painless. The same topic that seemed impossibly complex and upsetting at night was easy after we slept and ate. That made us pause and rethink what was going on.

We soon realized what most of our arguments had in common:

[Our fights] were happening after ten in the evening.

We didn’t fight because of our different values. We fought because we were sleepy, hungry, and therefore cranky.”

This led Tania and Brian an unexpected solution: “The Ten O’Clock Rule.”

“In short: we can’t bring up any serious or contentious topics after ten in the evening. And if one of us tries to pick a fight, the other just says “ten o’clock!” and all bickering must stop.

The rule has been our best problem solving tool, and has gotten us through nearly a decade of a very happy marriage :-)” 6

2. Other people: Who else has beaten the ocean?

In the 1990s, Oakland Athletics was one of the poorest teams and worst-performing baseball teams in the US. They had no budget to pay for winning players. And without winning players, they struggled to sell tickets to their games so they could raise their budget.

It was a perfect Catch-22.

Getting a larger budget was an ocean problem – they couldn’t do anything to change that. So Sandy Alderson, Oakland’s manager, instead focused on bright spots:

“What players scored many runs despite a low salary?”

So he dove into the piles of old score statistics, and there he found something interesting:

The power-hitters, the players who hit the ball the furthest and who everyone treasured, were actually not all that productive.

The players who scored most runs were those who could just get on base before they got tagged out.

A player who could reliably get on base may not score as many runs in one go. But by not being tagged out, they had the opportunity to keep scoring more runs again and again.

And the best part – these reliable players commanded much lower salaries. They just seemed less impressive at first glance, so few teams were bidding on these players. Alderson was the only manager to actually compare the data. 7

When you can’t find a solution yourself, look for other people who have succeeded despite the same ocean you face. Quite often, these bright spots will be fond in “dull” statistics and “boring” history books.

3. Analogies: Who else has beaten a similar ocean?

In 1989, an Exxon oil tanker struck a reef and dumped its oil into the Prince William Sound. When oil and water mix in cool temperatures, it morphs into a thick, glue-like substance like honey that is incredibly hard to remove.

The clean-up crew had a tough problem:

Once oil has been skimmed into a recovery boat, how do you pump the glue-like substance out of the boat?

No one had yet solved this challenge, despite the best efforts of many experts.

Then one chemist, Davis, cracked the code by borrowing a solution from a similar challenge: how to keep wet concrete from hardening.

Years earlier, Davis had helped a friend build an outdoor staircase of concrete steps. As concrete was unloaded, Davis was concerned to see how fast it began to harden in the scorching sun.

But then his friend’s brother came over with a concrete vibrator – a metal rod attached to a hand-held motor.

As soon as the shaking rod touched the surface, the concrete turned fluid instantly. The vibrations prevented the concrete elements from fixating.

Davis realized that concrete vibrators could also be used for oil recovery boats – thus turning their sticky oil payload into fluid when it had to be pumped out. 8

Borrowing analogous solutions can be powerful. But they are hard to find precisely because they come from a different field.

The key to finding analogous solutions is to first break the problem down into its universal form.

Universal form means that you look beyond the specific details of the situation, and instead focus on its general structure and characteristics.

Let’s take the oil-spill problem as an example:

Specific form: “How can we pump out oil-water mixture from oil recovery boats?”

Universal form: “How can we easily remove a thick, sticky substance?”

When framed in this universal way, your mind opens up to all manner of fields where thick, sticky substances need to be handled. Some examples are:

Accumulations of fat in water pipes 🚰

Glue residues from price tags 🏷️

Distributing honey into jars 🍯

And yes… concrete in construction 👷🏻

Look at situations with universally similar characteristics, and you are likely to find an ingenious solution to borrow.

Closing

When you know how to reach your desired destination, it ceases to be a “problem”. What is left is just the work of implementing it.

The problem is not the ocean stopping you – because you can’t do anything to change it.

The real problem is the fog – that you can’t see which action is best to take. Amidst the fog of reality, bright spots provide the guiding light to move forward with clarity.

Now, finding bright spots and studying what they do differently is hard work itself.

But what’s the alternative?

Give up on improving our lot in life?, or

Battle against the vast, foggy ocean with no light to guide you?

Either approach just leads to more dissatisfaction or work in the end.

The next time you find yourself on the shores of an overwhelming challenge, don’t look down at the dark waters below.

Instead, turn your gaze up and look for the bright spots on the horizon. And don’t be surprised when they come from an unexpected source.

The island you seek may be much closer – and may be very different – than you initially thought.

Thanks for reading,

Henrik Angelstig

Switch: How to Change When Change Is Hard - by Chip and Dan Heath

What’s Your Problem? – by Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg

Switch: How to Change When Change Is Hard - by Chip and Dan Heath

The 4 Disciplines of Execution – by Chris McChesney and Sean Covey

What’s Your Problem? – by Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg

The 4 Disciplines of Execution – by Chris McChesney and Sean Covey

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World – by David Epstein